You might call him a skillful negotiator, fighting for equality with peaceful talks and yellow ribbons. But don’t imagine rainbows and butterflies. There were some volatile times that were right on the edge and could easily have tipped toward more violence.

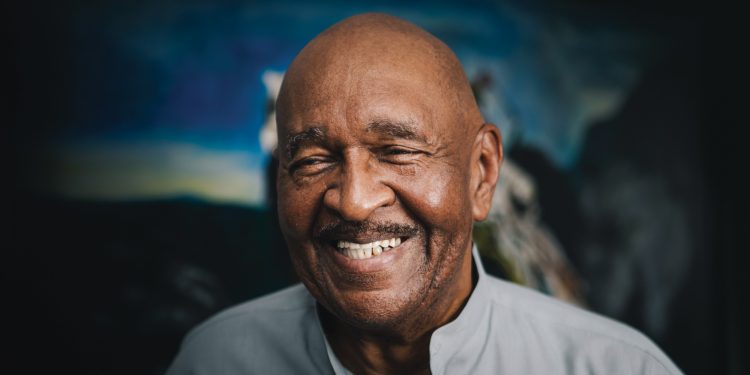

But Richard Brown says his life’s calling is to work for justice. It’s what he’s always done and continues to do. In fact, his 50 plus years (and counting) spent fighting for racial equality have earned him a rightful place in the Kentucky Civil Rights Hall of Fame, four terms on the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights Board of Commissioners, and Brescia University Distinguished Alumni, just to name a few recognitions.

But it all started with a decision point in Germany.

After graduating from Western High School here in Owensboro, Brown spent three years in the military, and was offered a chance to re-enlist and receive a large bonus to head to Vietnam in 1965. But the news from the States made him rethink things. “To see the marches going on back home with dogs and fire hoses being used on people and all that craziness going on. It was real. I saw white prisoners of war who were being treated better than blacks in our own country at the time. So did I want to fight for freedom overseas or did I want to fight for freedom in my own country?”

Brown decided to join the fight back home, so as soon as he got settled in Owensboro after a small stint in New York, he joined the local chapter of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

As racial tensions flared across the country in the late 60’s, Owensboro had its share of turmoil, as well. When a riot in 1968 caused police to heavily patrol black neighborhoods, Brown used his influence as a local and statewide leader of the NAACP to calm the situation and prevent further violence. Brown, along with several Catholic priests and other community members who were active in the civil rights movement in Owensboro, organized to make a list of concerns, and asked Mayor Irvin Terrill to join them for a conversation, which he did. A follow-up meeting at the courthouse served as another listening session to raise concerns. “The result was that our issues were then known by city leaders, and were later addressed. Things such as hiring black school teachers, hiring blacks for public service positions, and strained police relations,” Brown recalls.

As the 70’s came around, Brown continued to push for more hiring of minorities in Owensboro city government, which resulted in the hiring of the city’s first black firefighter in 1971, which happened to be Richard’s brother, Charles.

Brown graduated Brescia College (now University) in 1972, and still gives credit to several religious sisters on campus. To this day he calls Sr. Anna Louise his “guiding light.” Brown recounted in a 2013 interview with WKU Public Radio how Sr. Anna Louise formed a diverse group called “Operation Understanding” that brought together people from different backgrounds and races to openly interact in social situations. “She taught us that if you got an understanding beyond the skin color, you better understand the hearts and minds of those that are different than you.”

Brown graduated Brescia College (now University) in 1972, and still gives credit to several religious sisters on campus. To this day he calls Sr. Anna Louise his “guiding light.” Brown recounted in a 2013 interview with WKU Public Radio how Sr. Anna Louise formed a diverse group called “Operation Understanding” that brought together people from different backgrounds and races to openly interact in social situations. “She taught us that if you got an understanding beyond the skin color, you better understand the hearts and minds of those that are different than you.”

He gleaned skills from those experiences to help the NAACP address threats and racist protests toward black coal miners in Western Kentucky, and helped the Daviess County Board of Education recruit minority teachers.

It was Mayor C. Waitman Taylor who suggested Brown should get more involved in the community. “He told me, ‘People listen when they know you.’ I found that to be easier. It’s being proactive, rather than reactive. That was when people in city government started calling for me to help represent minorities and bring parties together. My way to go about it was to get involved in the community through serving on boards and foundations like the symphony and RiverPark Center so that when it came time to be heard, people knew me and respected me and would listen.”

And that became one of the guiding principles of Brown’s life. In fact, when I asked him what advice he might offer a 25-year-old, he simply said, “Get out there. Get to know people. Also, you have to know who you are as an individual and what you want to achieve before you can go out and work to accomplish it. Come together. Make a list of concerns. Work together for the good of the community. Then we have a place to start the conversation. Rather than wait for a problem to come to us and deal with it then, let’s come together and hit it head on. Church leaders. School system personnel. Other community leaders. That’s how you build your community.”

If he had to prioritize his main community concerns, he says it would be housing and hiring. “I always believe if you have a decent job and you can feed your family—it’s about the dignity and respect you feel.”

That is why he founded Owensboro Career Development Association Inc., which, in its heyday, organized field trips for area youth, supported travel abroad, and provided college scholarships. Today, the association utilizes an endowment to award scholarships each year. He says the goal is starting early to instill a sense of self-respect. “If there’s one young person we can convince to go to college or trade school, that’s a success.”

Another accomplishment that certainly became a factor in Brown’s awards and recognitions is his role in helping Owensboro residents resist a demonstration by the Ku Klux Klan. Brown and other city representatives came together and talked through a plan. Residents wore yellow ribbons to represent community unity rather than division, citizens were asked not to go downtown and demonstrate in hopes of upholding the peace, and several downtown businesses decided not to open that day. What was intended to be a large, confrontational rally was basically a non-event with plenty of police on hand to monitor the situation.

Even though he never set out to win an award, Brown says being inducted into the Kentucky Civil Rights Hall of Fame is something he is very proud of. “To be recognized by leaders all across the state for my actions in the NAACP was a high point for me because sometimes the hardest thing is to be recognized by your own community. That’s why I’m so thrilled to be selected for the Hall of Fame and as a Brescia Distinguished alumnus, too.”

Even though he never set out to win an award, Brown says being inducted into the Kentucky Civil Rights Hall of Fame is something he is very proud of. “To be recognized by leaders all across the state for my actions in the NAACP was a high point for me because sometimes the hardest thing is to be recognized by your own community. That’s why I’m so thrilled to be selected for the Hall of Fame and as a Brescia Distinguished alumnus, too.”

Now retired from a correctional facility as assistant district supervisor, Brown enjoys keeping up with his three children, eight grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. He and his wife of 57 years, Patricia, work out at the YMCA and run errands together most mornings. Richard is quick to give Patricia thanks, praise, and admiration for supporting him and making sacrifices so he could do what he did in the movement. It meant being away from his family for lots of meetings and appointments to committees.

He just rotated off his fourth appointment to Kentucky Human Rights Commission, but remains President of Owensboro Career Development Association, a trustee at Brescia University, and says he’ll be a local member of the NAACP until his dying day. “I’ll never give up my association. It’s the oldest civil rights organization in the country. I still feel proud.”

“Now at 75, I’m satisfied with the route I chose. My route isn’t for everybody. But I’m at peace. I want my children to have it a step better than I had it. They won’t have to be subject to name calling and segregation and degradation like we had it. That’s why I chose to stay in Owensboro. I like to think I helped open the door for this generation and the next.”