As another Memorial Day passes, and we remember those who have fallen and were lost in battle, we must also remember those who are still with us. There is a generation of men that our children need to know. These men are their grandfathers and their great-grandfathers. These men entered into a grisly war when they were not much more than children themselves. Their lives were forever changed, and they were left with silent stories to carry and brothers they have either lost or kept for life.

VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) Post 696 sits at the west end of Smothers Park, proudly overlooking the Owensboro riverfront. The VFW is a tightly -knit family of men and women who have been “honorably discharged from the U.S. armed forces, who have earned an overseas campaign medal,” and had their “feet on the ground in a combat zone” for thirty days or more. Within these walls are the stories of many men from many wars.

The president of the Ladies’ Auxiliary, Jessie Hettinger, pours her heart into veterans every day in an effort to honor the memory of her uncle Robert Wright, who is still considered MIA (missing in action) from the Korean War. Walter Duke spent twenty-two years in the Army, served in the infantry during the Korean War, and then went into the Army aviation program to be a pilot. Walter retired from the Army as a Lieutenant Colonel and, at eighty-three years old, still owns and flies his own airplane, and treasures the lifelong friendships that he has with his brothers at the VFW.

What is most amazing about these men is the amount of respect and admiration that they have for each other. Amongst the humor and the constant jabs for who had the guts to enlist and who was “invited” (drafted), there is an unspoken bond. One man will not hesitate to minimize his one tour in Vietnam against that of the man (Billy Milan) that did four tours and proudly wears a jacket to record his time on the famed “Hamburger Hill.” Yet, this morning, there is one man they wait for, that warrants their respect, for he is now one of very few that can stand and say he was there.

Delmar Freeman

Like most boys in high school during World War II, Delmar Freeman wanted to join the military and fight for his country. He planned to join the Marine Corps, but his mother and father refused to sign for him. Again, like most young men, he was drafted anyway, but this time by the United States Navy. Delmar was not yet 18 and in the 11th grade when he joined the Navy as a Boatman’s Mate. Although the others in the room joke that he spent his entire time in the service sweeping the deck of the ship, Delmar says that there were several times that he had to man and fire a gun. Yet the scariest time aboard ship had nothing to do with enemy fire, but more to do with the enemy of nature. In October of 1945, Typhoon “Louise” made a path for Okinawa, damaging and destroying many boats in its path. Delmar recalls the rough waters and says of the experience, “(We) almost lost our ship, but we rode it out.”

After returning home from the Navy and the war, Delmar lived in Paducah, Kentucky and then went on to work for Hudson Motor Car Company in Detroit, Michigan. This is where he met his beautiful bride of sixty-six years, Gertrude. Twenty-four years ago, he retired from the Iron Workers Local 103 in Evansville. The men at the VFW seem to have almost as much admiration for his iron work as they do his military service. They sit in awe and say, “He built skyscrapers without safety harnesses or anything.” Whether it is for his military service or his bravery as an iron worker, Delmar, now eighty-nine, is still active in the VFW, and is a man and a veteran to be admired.

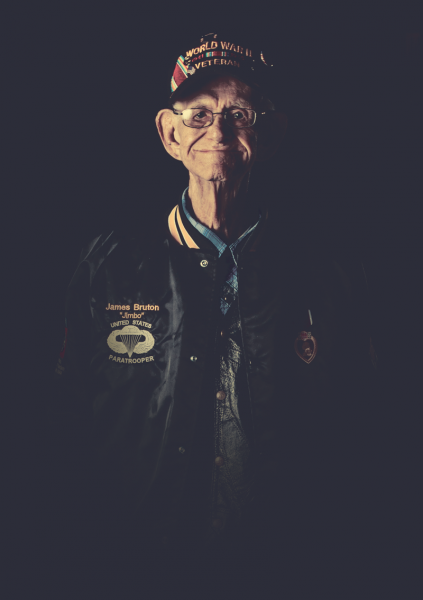

James “Jimbo” Hall Bruton

Another WWII veteran that is revered at Post 696 is Jimbo Bruton. James “Jimbo” Bruton grew up in the hills of Burtchville, Kentucky. By the time he reached high school, he weighed one hundred ninety pounds, was six foot three inches tall, and “played every sport there was.” In fact, Bruton says that his presence in a crucial football game in Bowling Green “cost me from being drafted. I was just turning 18, and a bunch of my buddies and I were going to join the Navy.” He thought the Navy would offer him a better chance for advancement, but a very persuasive Army Sergeant said to him, “Join the Army and see how fast you advance, boy.” Never one to back down from a challenge, Bruton became an Army paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne. After routinely jumping with ninety-eight pounds of equipment on his back, including forty-two pounds of parachute, Bruton says he “went up seventeen times before I realized one could land.” Jimbo recalls going through paratrooper school with late actor William Windom. Bruton says of their different paths after the war, “He became a movie star. I was good with my hands.”

Another WWII veteran that is revered at Post 696 is Jimbo Bruton. James “Jimbo” Bruton grew up in the hills of Burtchville, Kentucky. By the time he reached high school, he weighed one hundred ninety pounds, was six foot three inches tall, and “played every sport there was.” In fact, Bruton says that his presence in a crucial football game in Bowling Green “cost me from being drafted. I was just turning 18, and a bunch of my buddies and I were going to join the Navy.” He thought the Navy would offer him a better chance for advancement, but a very persuasive Army Sergeant said to him, “Join the Army and see how fast you advance, boy.” Never one to back down from a challenge, Bruton became an Army paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne. After routinely jumping with ninety-eight pounds of equipment on his back, including forty-two pounds of parachute, Bruton says he “went up seventeen times before I realized one could land.” Jimbo recalls going through paratrooper school with late actor William Windom. Bruton says of their different paths after the war, “He became a movie star. I was good with my hands.”

Unfortunately, those hands were put to use by the Germans to repair railroads “that had been damaged by Allied bombs.” Bruton was one of many American paratroopers that were captured and held as POW’s (Prisoners of War) at Stalag compound in Linburg, Germany. Bruton earned his Purple Heart the day he was captured by suffering a minor wound to the leg. He went on to spend over eight months at the prison camp, much of which is documented in Claire E. Swedberg’s book Work Commando 311/I. The book chronicles the personal accounts of several men at the compound, including Bruton. Documented in the book is the story of how a gruff guard saved him from gangrene with a set of pliers, and the infamous story in which he took down a low-flying WWI bomber plane with his athletic arm and a large rock.

Bruton credits his Kentucky upbringing with helping him to escape from the German POW compound. “I was born in the hills, so I was good at that. When they weren’t looking—I just slipped off.” After being declared MIA for over eight months, he managed to escape over the course of eleven days and nights. Bruton says of his military service, “I’ve been through all that stuff…and I’d go again tomorrow.”

Fred L. Ward

Fred Ward was born and raised in Whitesville, Kentucky and enlisted in the United States Marine Corps at age 17. However, you will not find Mr. Ward at VFW Post 696. Instead you will find him proudly wearing his red satin Marine Corps jacket and uniform hat, gracing the hallways of a local full-time care facility. His daughter Carolyn says that the whole experience has been a blessing, as everyone at the facility has gone out of their way to show honor and respect for Mr. Ward’s WWII military service. Alton Neagle, a Vietnam Army veteran and social worker at the facility, struck an immediate bond with Mr. Ward. Carolyn says that “The bond he and Daddy have is very, very special” and it “puts peace in my heart” to know there is someone there that cares for him in that way.

Up until very recently, Mr. Ward was able to clearly share his wartime memories as if they happened yesterday. At the age of seventy-eight, he began requesting legal pads in an effort to free memories that had plagued his mind for nearly sixty years. He finally filled enough legal pads to publish the book Picking Up the Pieces: The Battle of Iwo Jima. In the book, Ward chronicles the horror he experienced as a nineteen-year-old Marine “on a tiny island that lay in the Pacific Ocean only 750 miles from Tokyo, Japan…so small I could ride my bicycle in any direction approximately 30 minutes.”

Ward landed on the island on February 19, 1945 and was part of the original forty-man team that raised the first flag atop Mount Suribachi on February 23. Mr. Ward recalls, “The first flag was too small so we went to a ship (aircraft carrier) to get a bigger one.” This bigger flag is the one we have come to know from the now-famous picture. Five days after raising the flag, Ward was shot in the calf, earning a Purple Heart, and two weeks in the island infirmary. Ward was one of thirty-two men that were wounded or killed out of the original forty-man flag-raising team. When asked now why they raised the flag that day, he said it was to let the enemy know that “they better scoot or give up real quick.”

In October of 2014, the same year of the seventieth anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima, Fred Ward was among those selected to fly to Washington through the Honor Flight Bluegrass program. Alton saw to it that Mr. Ward received a full motorcycle escort to the Sportscenter before departing on the bus for Washington, D.C. Of the experience, Carolyn recalls, “before I could even get the wheelchair stopped, he was up out of that chair saluting that monument.” In reality, it is these men that risked their lives so many years ago, that we should all be saluting.

[tw-divider]WORLD WAR II VETERANS[/tw-divider]

The median age for World War II veterans is 96 years of age.

According to statistics released by the Veteran’s Administration, “our World War II vets are dying at a rate of approximately 492 a day. This means there are approximately only 855,070 veterans remaining of the 16 million who served our nation in World War II.”

Kentucky had nearly 11,000 WWII veterans at of the beginning of 2015.

For further information on these gentlemen and their stories, read Work Commando 311/I by Claire E. Swedberg, available on Amazon.com, and Picking Up the Pieces: The Battle of Iwo Jima by Fred L. Ward, available on Kindle and through Amazon.com.