Many of us welcome the new year of 2023 with resolutions to improve our overall well-being. We promise to stop smoking, improve our diets and get more exercise.

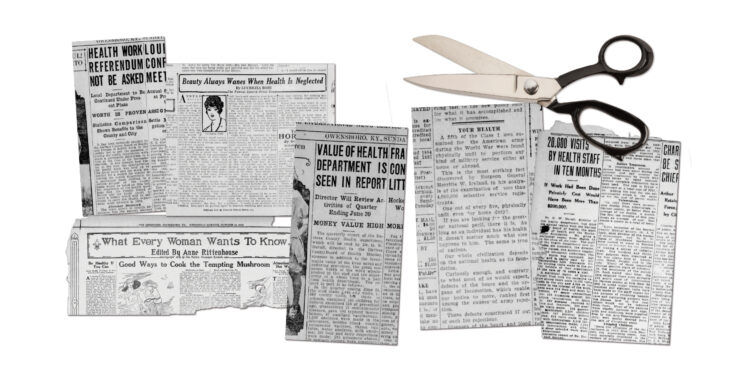

Our ancestors of 100 years ago were also thinking about health and wellness, but while their goals may have been similar, their specific areas of concern, and their methods of initiative were very different.

First, there was a kerfuffle about who would oversee public health in our community. A newspaper article published on Feb. 24, 1923, announced that the establishment of the Daviess County Board of Health “didn’t meet law.”

It seems that fiscal court had established the local board of health in 1919 – at which time it adopted a resolution to appropriate $5,000 a year toward its maintenance, with a matching amount to be granted by the state board of health. However, the appellate court in Frankfort determined that the health department had not been established at a regular meeting, as required by law.

The issue was eventually resolved, of course, and later that year, the Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer reported that the Daviess County Board of Health’s “worth is proven.”

From March to December, the board had documented 20,000 nursing visits by its staff. In addition to those visits, which were valued at the rate of 75 cents a call, were a wide spectrum of services such as food and dairy inspections, inoculations, smallpox vaccinations, quarantine visits, detection of physical defects and other “splendid work,” and altogether would have cost $200,000 if the work had been done privately.

Rabies treatments alone were valued at $33,750.

Records also documented 134 “suspects” being examined for tuberculosis at free clinics in Knottsville, Habit, Sorgho and Owensboro, with 30 of those examined showing “definite signs of infection.” An examination of data concluded there were probably about 500 active cases of TB in Daviess County.

“As will be noted under statistics,” a newspaper article reported, “six hundred and eighteen visits have been made by staff nurses for the purpose of rendering bedside care and instructing patients with the disease how to live that others would not be infected by them. Many of the patients were charity patients and eggs, milk and medicines were supplied free by the Anti-Tuberculosis society, with money derived from the sale of Christmas seals.”

Time has a way of putting a lot of things in perspective, including what seems to us today to be an alarming statistic that was presented as relatively “good news” 100 years ago: The infant mortality rate in Daviess County was “only” 75 per 1,000 births for the first 10 months of 1923. Statewide, the childhood mortality rate showed that 65 percent of those died during their first month of life.

But children weren’t the only ones with worries about health and wellness.

Ladies of the day were cautioned that “beauty always wanes when health is neglected” – but another (slightly more forward-thinking) article also directed toward the ladies scoffed at the notion that a healthy-looking female ran the risk of “looking like a peasant.”

Gone are the days, this writer trumpeted, when “it was quite pardonable and expected for the young girl to faint at dances or to be missing at dinner … because of a headache or a ‘slight indisposition.’”

Be careful, ladies, the writer warned: Men were watching! “The young girl employ(ed) to be your stenographer somehow makes a bad impression the first day if you see her taking digestive tablets after luncheon.”

Not that men were immune from criticism!

As reported in another article, one-fifth of the Class 1 men examined for the American army during the World War (back when there was only one of those) were found “physically unfit to perform any kind of military service either at home or abroad.”

“Defects of the bones and the organs of locomotion” were the most common causes of rejection, followed by diseases of the heart and blood vessels, diseases of the eyes … and tuberculosis.

Rhode Island ranked worst, as far as military recruits were concerned, with 42 percent of RI residents “so physically defective that they were rejected.”

There was a theory for this: Rhode Island’s “bad showing, according to experts, was due to being a factory state.”

The article concluded that “money-mad America thinks too much about its natural resources and industrial products, not enough about our greatest product – the human being and his health.

“Health should always come foremost. … Personal health is nine-tenths up to the individual.

“Get plenty of wholesome food, sleep, fresh air and outdoor exercise, and, barring the bad luck of incurring germ disease, health will be fairly good on the average. In particular, the auto driver should lock up his car and go about on foot at least one day a week.

“When health is gone, the rest doesn’t count for much.”

Hmm. Those closing lines have stood the test of time, with their advice as strong and healthy now as they were 100 years ago. OL