William ‘Bill’ Kolok’s journey as an educator and artist

Owensboro sculptor William “Bill” Kolok retired from Kentucky Wesleyan more than a decade ago and set his sights on one of his true passion: art. He converted a small home on Veach Road into a studio and added a shop to the rear of it.

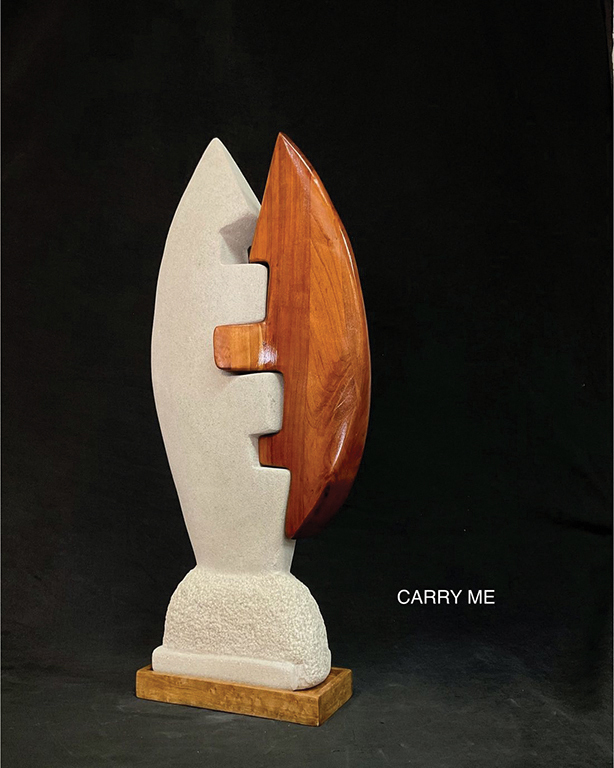

Kolok said it’s where artistry, hard work, and storytelling collide, and he goes to his studio every day. Inside the space, Kolok blends wood, stone, and metal into abstract sculptures that he hopes invite conversation. For Kolok, the finished piece is only part of the journey; the true reward lies in the process of creation.

Each November, Kolok opens his studio to the public, offering visitors a chance to experience his work and understand the world through his perspective. He said his art tells a story of conflict, harmony, and perseverance. But Kolok is quick to remind viewers that their interpretations are as valid as his own.

“I’m a storyteller,” he said. “You might see one thing in my work while I’m telling a completely different story, and that’s OK. That’s the beauty of art.”

Kolok’s journey into the world of sculpture was as unconventional as the pieces he creates. Growing up in a Slovak immigrant community in Connecticut, he was surrounded by blue-collar work ethic and small-town values. His father was a truck driver, and his mother worked in retail. Though he dreamed of becoming a forest ranger – living alone in a watchtower with a pet raccoon – his path took a sharp turn when he enrolled in a design class at Georgia’s Berry College.

“I wasn’t a good student,” Kolok admitted. “I applied to one college, and somehow I got in. That basic design class changed everything for me. It was easier than biology, but it also awakened a passion I didn’t know I had.”

That passion led Kolok to change his major to art, a decision that laid the foundation for a lifelong career. Determined to balance creativity with practicality, he pursued a dual focus in art and education.

“I knew I had to make a living,” he said. “I couldn’t just make art. I had to work.”

Kolok began teaching art in elementary and high schools before earning a Master of Fine Arts in sculpture from the University of Georgia. After a brief stint teaching at the University of the South in Tennessee, he accepted a position at Kentucky Wesleyan College in Owensboro in the late 1970s.

“I applied to 300 colleges that year,” Kolok recalled. “Wesleyan hired me just two weeks before classes started. It was supposed to be a stepping stone, but it became my home.”

For four decades, Kolok educated aspiring artists while pursuing his own craft on the side. He estimates he created eight or nine pieces per year during his teaching career.

“Back then, I worked three hours a night in a small studio at home or in the college facilities,” he said. “Now that I’m retired, I’m able to fully focus, producing 20 to 30 pieces annually.”

Kolok purchased his studio five years before his retirement. The building required significant renovations, including new floors and insulation. Today, it’s a sanctuary where Kolok spends hours each day immersed in his craft.

“Here, I make all the decisions. It’s a space that reflects my passion and my independence,” he said.

For Kolok, the act of creation is a labor of love.

“Once a piece is finished, it’s dead to me,” he said. “It’s the cadaver of creativity. I’m more interested in the process, the noise, the dust, and the challenge of making something new. That’s what excites me.”

Kolok’s art often combines materials – wood, stone, and metal – in ways that explore tension and harmony. He sees this fusion as a metaphor for life.

“Art is about conflict and balance,” he said. “It’s about showing that you can live in both worlds – the real and the creative – and make them work together.”

Kolok acknowledged that Owensboro wasn’t a major market but said he has found an appreciative audience. His November open houses attract locals, while galleries in Louisville and Lexington, as well as collectors from across the country, provide a broader platform for his work.

“There are maybe half a dozen people here who collect my pieces,” he said. “I’m grateful for them. But most of my sales come from outside Owensboro.”

Kolok’s story resonates with those who value hard work and perseverance. He believes art isn’t about natural talent or financial success; it’s about dedication.

“You don’t have to be rich or famous to make art,” he said. “You just have to want it and work for it. That’s what my work represents.”

Despite the challenges of being an artist in a small town, Kolok wouldn’t trade his journey for anything.

“At the end of the day, I go to bed tired but fulfilled,” he said. “That’s all I can ask for.”

Kolok’s influence extends beyond his own work. Many of his former students have stayed in touch, continuing to create their own pieces while juggling other careers.

“I always told them, if you can do anything else, do it. But if art is your calling, then you do it, no matter what,” he said. “This is the love of my life and the bane of my life. But I wouldn’t have it any other way.” OL