C.G. Morehead’s legacy lives on through family, art, and a life richly painted

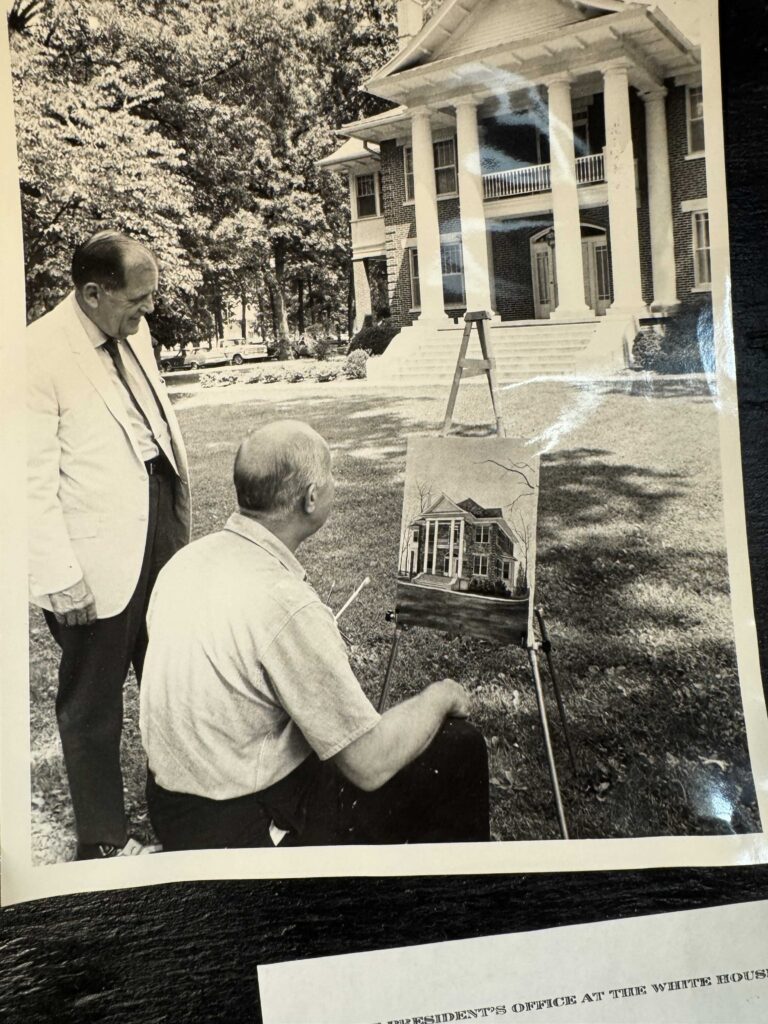

Renowned Owensboro artist C.G. Morehead never set out to become famous. He was simply a man who loved to paint. But according to his son Robert, that love carried the late C.G. far beyond Kentucky, even to the White House.

C.G.’s paintings found their way into the hands of presidents, country music stars, and collectors across the nation. He met Jimmy Carter in Washington, mingled with performers including Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, and Minnie Pearl at the Grand Ole Opry, and even received a handwritten note from actress Agnes Moorehead of “Bewitched” thanking him for his art.

Among his most talked-about pieces was a painting mixed with peanut butter — a playful experiment that ended up raising more than $10,000 for charity after President Carter personally signed it.

“He used to joke that he found a way to make lunch and art at the same time,” Robert said of his dad.

Those stories hint at the caliber of the man whose legacy still fills the Morehead home with color, history, and warmth.

C.G. didn’t begin painting until his mid-40s, after a career in real estate and state work that included helping secure land for Kentucky’s parkways under Gov. Ned Breathitt. Once he picked up a brush, he never stopped. For nearly two decades, he produced hundreds of detailed oil paintings — landmarks, horse farms, and southern scenes rendered with precision and heart.

“He’d take pictures, make sketches, and count how many bricks were on a building,” Robert said. “He knew the dimensions of everything. That’s why his work had so much detail — every piece meant something to him.”

C.G. painted slowly, often spending four months on a single canvas. He built a studio addition to his home off Ford Avenue and worked deep into the night, moving from dinner straight back to his easel.

“He wasn’t one to fish or hunt,” Robert said. “He painted every day. That was his way to relax.”

His attention to accuracy was matched only by imagination.

“If someone said they didn’t remember that building being there,” Robert said, “he’d laugh and say, ‘That’s an artist’s privilege, I can put a building wherever I want.’”

Though he became known nationwide, C.G. remained humble. He was part of the Kentucky Heritage Artists, a group of prominent painters in the 1970s, and was later invited to the Fine Art Trade Bureau in London after completing a painting of 10 Downing Street. He often gifted prints instead of selling them, preferring to share his art freely with those who admired it.

When he traveled, he took inspiration from everywhere.

“He’d meet someone, tell a few stories, and before long they’d be asking him to paint something for them,” said his daughter-in-law, Sarah Morehead. “He just connected with people, whether it was a farmer in Kentucky or someone famous at the Opry.”

Beyond his artistic life, C.G. was a World War II veteran whose experiences deeply shaped his outlook. He served as a platoon leader in Germany and France, tasked with clearing villages of hidden enemies.

“He didn’t talk about it much until I was grown,” Robert said. “He told me he’d been in a jeep with another soldier nicknamed Frog, and a sniper’s bullet took Frog’s head off right next to him. He said it was constant, people getting killed every day. But he made it home.”

Those years abroad gave C.G. a deep appreciation for life, which later came through in his art.

“He’d seen enough darkness,” Sarah said. “Painting was his light.”

When he returned home, C.G. built a new life in Owensboro — first in real estate, then in art. His works depicted everything from the University of Kentucky Administration Building to Churchill Downs and the Grand Ole Opry, each painted with the same care and depth that defined his life. He met influential figures through his art, including Senator Wendell Ford, who helped arrange some of his visits to the White House and introduced him to other public figures.

Those connections never changed who he was.

“At heart, he was just a Kentucky man who liked to paint barns and pretty scenes,” Robert said.

The Moreheads’ home is filled with his work. Each one is both memory and legacy.

“When we found out one of the barns he painted had been torn down, the owner let me take boards from it,” Robert said. “Now those frames hold part of his history.”

Even the stories behind the paintings are as vivid as the colors on the canvas. His wife appeared as a background figure in one of his Grand Ole Opry paintings — a private joke C.G. added to amuse her. She loved it.

“He said, ‘See that white-haired woman in the doorway in the black dress? That’s my wife,’” Robert recalled.

C.G. passed away at 58 from lung cancer, leaving behind an unfinished painting of the Alamo — brushstrokes frozen mid-line, a poignant reminder of a life that, though short, left color everywhere it touched.

“We thought about having someone finish it,” Sarah said. “But it felt right to leave it as it was. It’s part of his story.”

After his death, C.G.’s wife lived another 30 years in their Owensboro home, often walking visitors through the collection and retelling the stories behind each painting. The night before she died from an aneurysm in 2009, she took Robert and Sarah through the house one last time, explaining the stories behind each piece.

“She wasn’t sick. She was completely herself,” Robert said. “And the next day she was gone. It was almost like she knew it was time to tell those stories one more time.”

Sarah added, “She never remarried. She just loved him and what he created.”

Tucked among the paintings are note cards written in C.G.’s own hand — simple lines that reveal his philosophy on life and art. One reads, “Art should be for fun and enjoyment.” Another says, “Anyone who can hold a paintbrush can learn to paint.” Robert keeps them close, reminders of his father’s gentle wisdom.

“He used those during speaking engagements,” Robert said. “They really captured who he was.”

CG’s art continues to hang in homes and galleries across the state and country, but it’s within his family that his spirit endures most vividly.

“He was a very interesting man,” Sarah said. “He did a lot in just 58 years.”

Today, Robert and Sarah continue to share his work and his story.

“We love having all the art,” Sarah said. “It would hurt to let it go, but we also don’t want it to end up in an attic someday.”

They plan eventually to pass a few of the most recognized works, like the Churchill Downs painting, to other family members or collectors who appreciate his talent.

“Dad always said it didn’t matter what you painted — fruit, barns, or people,” Robert said. “As long as you painted something that made you happy.” OL