Osborne’s story of survival and forgiveness through faith

Photos by Jamie Plain

David “Oz” Osborne can still remember the horror of thinking he was about to die when a man pushed the hot barrel of a .38-caliber revolver to his forehead and pulled the trigger. Luckily for the 33-year-old Osborne — who was lying on the ground, paralyzed from the waist down from four bullet wounds already — the hammer clicked emptily, as the man had already fired all five rounds. It took 10 years for one of the bullets to work its way through Osborne’s body and press against his heart, but his journey of recovery and forgiveness through faith began long before then.

A CALLING FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT

Osborne always knew he wanted a career in law enforcement when he was growing up. However, his early life was marked by tragedy. When he was just 11 years old, Osborne’s 3-year-old sister, Anne, was killed in a car accident. Following her death, Osborne’s parents became understandably cautious, dissuading him from pursuing a career in law enforcement or any related field.

Despite their concerns, Osborne pursued his interest in serving the community — but they directed him toward a different path: the Methodist ministry. He attended the University of Kentucky for two years before transferring to Kentucky Wesleyan College, a Methodist school. He enjoyed his time there, and ultimately settled in Owensboro.

In 1982, Osborne got the chance to fulfill his dream when he was hired to work at the Daviess County Sheriff’s Office.

“I was so eager that I would have paid them just to let me work there,” he said. “That’s how much I wanted to be part of it.”

After 7 years, Osborne was offered a K-9 dog named Bill. Not long after, Osborne’s life changed dramatically.

THE CALM BEFORE THE SHOOTING

On May 27, 1989, Osborne decided to swap his usual midnight shift for a mid-shift assignment. He was tasked with delivering a restraining order to Darrell Perry at a residence in the 9700 block of Old Hartford Road, near Pleasant Ridge. The order required Perry to vacate his home.

According to Osborne, Perry was involved in a family dispute: Perry was 53 years old, and his 70-year-old wife — who had recently been diagnosed with terminal cancer — altered her will to leave everything to him; Perry’s wife’s daughter was contesting the change, claiming her mother wasn’t in the right state of mind.

Shortly after 8 p.m., Osborne parked behind Perry’s car and approached the house. When Osborne knocked on the door to serve the papers, there was initially no response.

Osborne said he typically refrained from disclosing his location over to dispatch due to the high volume of cases he handled. That night, something compelled him to call dispatch to provide his exact address — a decision that would later prove crucial.

After the call, Perry eventually answered the door. Osborne still remembers the sight: standing at approximately 6 feet tall and weighing approximately 250 pounds, Perry was a large man with a full beard, dressed in a white T-shirt, green pants, and white socks, with no shoes on his feet.

Osborne informed Perry that he was there to deliver papers requiring him to vacate the house immediately. Osborne explained that Perry was allowed to take only his toiletries and a few articles of clothing.

“Why is this happening to me?” Perry repeatedly asked as Osborne read the orders to him. Osborne explained he was merely executing his duties and not involved in the decision-making process.

Osborne said the interaction felt routine, as sheriff’s deputies frequently serve civil papers. Perry didn’t act belligerent or angry.

As they walked toward the end of the driveway, the sky darkened, and Osborne ensured Perry did not take anything beyond what was permitted. Osborne said the county attorney instructed him to ask for the house keys, but Perry checked the order and noted that handing over the keys was not required, so he refused to do so.

Osborne wished Perry a good night, seemingly marking the end of their interaction. In those moments, Osborne said, there never appeared to be a threat.

“We didn’t argue, and he never raised his voice,” Osborne said.

TRAGEDY STRIKES IN AN INSTANT

Osborne heard the first gunshot as he reached for the door handle to his cruiser. He turned to see Perry standing with a .38-caliber revolver that he grabbed from his car. The first round went through Osborne’s left arm, into his left side, across his abdominal area.

“I never felt it,” he insisted, recalling how he instinctively shifted his focus to Perry, who was in a weaver stance, one foot in front of the other with both arms holding the gun, about 10 feet away.

As Osborne turned to seek cover behind his cruiser, Perry fired again. The sequence unfolded in a matter of seconds. The second shot struck Osborne in the left flank and lower back, cutting a portion of his spinal cord, which left him paralyzed at the time from the waist down.

Osborne fell to the ground. Perry kept firing.

The next shot hit Osborne in the left buttock, and the last went through his shoe and penetrated his heel.

“The only shot he missed me with was through the brim of my campaign hat because I had my head down,” Osborne said.

Perry lunged at Osborne, pinning his arms back with his knees.

“He took the revolver, cocked it, and pressed it to my forehead, pushing my head back into the gravel driveway,” Osborne said. “I just closed my eyes, thinking, ‘This is it.’”

Osborne heard the gun snap.

Perry looked at the gun and realized he’d shot each round in the five-shot revolver. He then held it like a rock and started hitting Osborne in the head. Osborne said Perry hit him more than 25 times with the weapon, fracturing Osborne’s skull and knocking out two of his teeth.

Finally managing to work his arms free, Osborne found himself in a desperate struggle for survival.

“I was fending him off,” Osborne said. “The whole time, I was just pleading, ‘Stop, what are you doing? Stop, stop.’”

Osborne managed to draw his semi-automatic pistol, but he unconsciously ejected the clip, something that unintentionally proved vital to survival.

“I tell people that was a God thing, because they don’t teach you in the academy to eject your clip if you are under fire,” he said.

There was still one bullet in the chamber, though.

“We were fighting, and I was trying to shoot him,” Osborne said, but the angle was difficult. “I just couldn’t get it turned because he was pushing me.”

Osborne managed to squeeze the trigger, and the gun fired between them. Perry twisted the pistol out of Osborne’s hand and immediately pointed it at Osborne’s head, pulling the trigger.

Click.

Perry tried to charge the gun again, pointed it back at Osborne’s head, and pulled the trigger once more.

Another empty click.

Perry then took the keys from Osborne’s belt and seized his radio. Perry crumpled the civil papers he’d been served and stuffed them in Osborne’s mouth, saying, “Here, how do you like that?” before climbing into the patrol car.

“At that point, I was ready for him to leave,” Osborne recalled.

Lying behind the cruiser, unable to move his legs, Osborne realized he was about to be run over. He was able to roll over on his side before Perry drove out into the darkness.

Throughout the events, K-9 Bill had been trying to get out of the car.

“He could see everything going on and I could just hear him barking like crazy, wanting to get out of that car,” Osborne said. “In those days, we didn’t have automatic door openers for police dogs like today. Officers had to manually roll down the windows for the dogs to exit the vehicle.”

According to Osborne, Perry later claimed he didn’t even know the dog was there until he was halfway into town and heard Bill growling.

“If Bill had gotten out of that car, he would have reached him,” Osborne noted. “But Perry was able to drive away.”

He said that Perry didn’t hurt Bill, and Osborne got to keep the dog for the rest of its life.

FEELING HOPELESS, HELP ARRIVES

As he lay in the driveway, Osborne felt a deep fear unlike any he had experienced before.

“I was just as scared as I’ve ever been in my life,” he said. “I cannot describe the horror when someone is trying to kill you.”

He felt the intensity of his injuries, with his legs seemingly sticking straight up in the air and a burning pain in his back.

“It felt like I had a hot poker stuck in my back,” he said, expressing the fear that he might die right there.

Osborne reflected on the teachings of his Christian upbringing.

“My mother always said, ‘If you’re scared, Jesus is always here. You don’t have anything to be afraid of.’ She knew the 23rd Psalm and told me to recite it,” he recalled. “I knew it, too, and I said it aloud. I told people, the God I know was right there with me. He didn’t say I was going to live or die; he just said, ‘I’m here, I’m here, and it’s okay.’”

Feeling an urgent need to signal for help, Osborne tossed his hat toward the edge of the roadway, but cars continued to pass by.

“I thought, I’m going to bleed out in this driveway,” he said, leading him to roll onto his stomach and drag himself to the road’s edge.

Then came a turning point, what he calls his good Samaritan story. Osborne said a couple, Clarence and Mary Hulsey, stopped to help.

“I can tell they were scared because I looked terrible,” he said. I told them to call 911 because I’d been shot.”

Meanwhile, dispatch had been calling his radio, attempting to reach Osborne with calls for help after he sent them his address. Then-deputies Paul Nave and Randy Ray were riding together that night and were the first to get to the scene.

Osborne doesn’t remember much else about that night after that.

ROAD TO RECOVERY, AND A BULLET RETURNS

Three days later, Osborne woke up in the hospital to the news that he would never be able to walk again, or have children. Doctors told him he would be confined to a wheelchair and not even have control over his bladder.

“At 33 years old, it was devastating,” he said.

Osborne was in the hospital for 8 weeks and then rehabilitation for another 8 more.

While in the hospital one day, Osborne discovered he was able to move one of his toes. After 7-8 months, he graduated from a wheelchair to crutches, to canes, and then the ability to walk with no support again.

Eventually, he resumed his career at the Sheriff’s Office. He got remarried and had three children.

“From that day to this day, I had no idea how much God was gonna bless me,” he said. “He has blessed me literally beyond my wildest imagination.”

Ten years after the shooting, while driving to work, Osborne felt like he was having a heart attack. He drove himself to the ER, where he learned the bullet that entered through his left side and was never found eventually made its way to his heart.

“That bullet had traveled up to my heart and pressed against my pericardial sac,” he said.

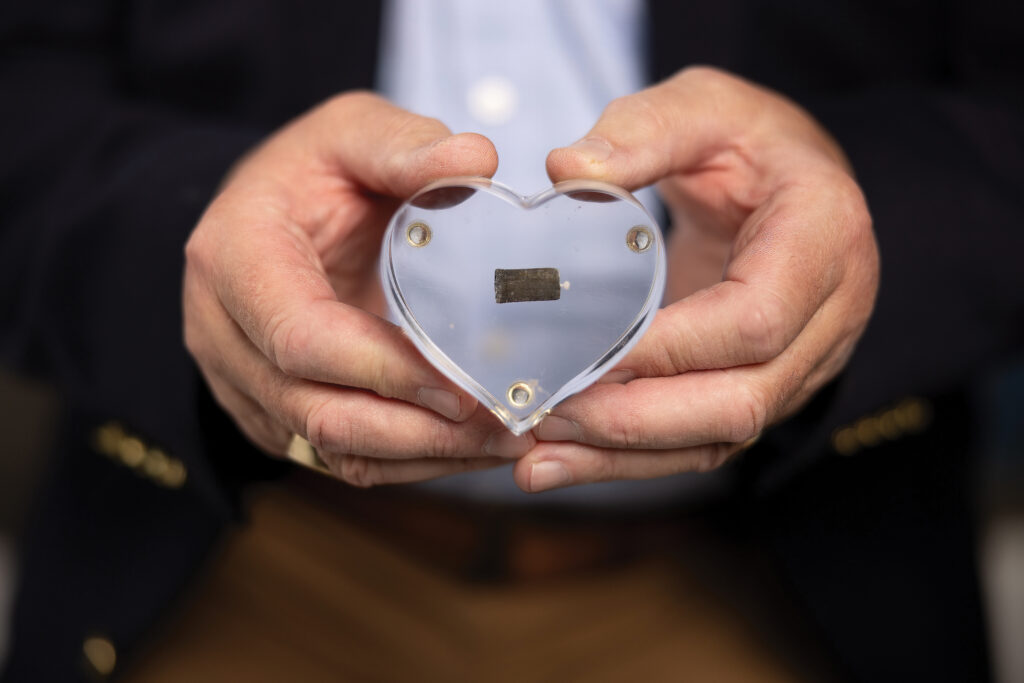

After surgery, Osborne’s wife put the bullet in a ceramic heart, which he still has to this day.

FINDING FORGIVENESS

According to Osborne, Perry went on the run following the shooting, searching for his former wife. After ditching the police cruiser on 18th Street, Perry attempted to find his step-grandson, whom he shot in the stomach at point-blank range.

Perry was sentenced to a total of 30 years for both shootings but ultimately only served 18 at the state penitentiary in Eddyville, Kentucky, a maximum-security facility.

“People say, ‘Well, 18 years was not enough,’ but go spend about a week in Eddyville and see if 18 years is enough time. It’s hard time,” Osborne said.

About a year and a half after Perry’s trial, Osborne received an unexpected call from the Commonwealth’s Attorney, who relayed that a letter from Perry had been addressed to him.

In the letter, Perry expressed remorse for his actions and sought Osborne’s forgiveness. Osborne was taken aback.

“I mean, literally I was like, ‘pow.’ So I just put it aside,” he said, noting that a feeling to respond persisted. “It was just constant. It’s like the good Lord was right in my ear, constantly saying ‘hey, he’s asking you to forgive him.’”

Osborne wrote back to Perry, affirming his forgiveness. Osborne said that the bitterness he held towards Perry began to dissipate. Osborne never saw or heard from him again after that letter. Perry eventually died in 2019 at the age of 81.

“It lifted me,” he said. “Forgiveness not only lifts the burden off the forgiver but it frees both of you when you’re able to do that. I knew he was sincere, and he didn’t have anything to gain by it.”

MAINTAINING GRACE

After 24 years, Osborne retired as chief deputy with the Sheriff’s Office. He was later elected Daviess County Clerk, retiring from that office at the end of 2018 with nearly 40 years of public service behind him.

Osborne has spoken to countless individuals over the years, including police recruits at the Louisville Police Department and at Eastern Kentucky University’s police academy. In 2000, Osborne graduated from the FBI National Academy, a prestigious management training program, becoming only the second person in the academy’s history to complete the physical agility course using a wheelchair.

Osborne’s story has resonated widely; a law enforcement television network even produced a reenactment of his shooting, titled “Serving Papers: The Hidden Threat.”

Despite the challenges he faced, Osborne remains grateful for the blessings in his life.

“People call me crippled. Well, no, I’m not a cripple; I’m a blessed man,” he said. “God has certainly used my injury to help me share my story. It is my testimony and my life’s story.”

Osborne now enjoys spending time with his grandchildren, who range in age from infants to 16 years old, and he works out at the Owensboro Health HealthPark several days a week.

Now in his seventies, Osborne remains a quiet pillar in the Owensboro community. Though he no longer wears a badge or holds office, his legacy continues — not just in accolades or career milestones, but in the resilience and grace with which he’s chosen to live his life.

He occasionally gives talks at local churches and civic groups, sharing his story — not to dwell on the pain, but to illustrate the power of forgiveness, faith, and starting again. OL